Imagine that you are enrolled in a math class at one of the most prestigious universities of the world.

You have an exam coming up real soon. Obviously, you want to perform well on the exam.

The thing about this university is that it has a clumsy set of professors. So cheating is really simple. You can easily copy from the guy sitting behind and ahead without getting caught.

The professors, in order to take control of this problem, came up with two solutions:

- The number of students sitting in a class is never fixed. And the people sitting in one class taking the test change from one test to another.

- The seating arrangement is released five minutes before the exam. The seating arrangement is alphabetical. But since the students are never fixed and new ones may get added or old ones removed from a class randomly, the arrangement has to be explicitly released for the students to know where exactly they have to sit.

Say you’re one of those lazy students who wants to cheat, despite the consequences. Five minutes before the exam when the seating arrangement is released, how do you find out who is sitting in front of you and who’s behind as quickly as possible?

You won’t be able to cheat if you don’t talk to these two people beforehand and strategize, right?

The Seating Arrangement

So the professors released the seating arrangement for the first test ever conducted this way. Say it had N students. If these students were to remain the same from one test to another, then it would have been very easy to cheat, right? Because the seating arrangement is always done alphabetically.

Therefore, the professors keep on adding or removing students from this list from one test to another, and only released these modifications before each test. This way, students could never know deterministically before a test who would be sitting in front of or behind them.

Let’s consider this problem in algorithmic terms. We are given a list of N elements where elements in this case are student’s names. This list keeps on varying from one exam to another, such that new elements can be added to the list or existing elements can be removed from the list.

Given the list of modifications at any given time T and a name N, we need to determine the elements B and A, such that B would come right before N and A would come right after N if the list were to be sorted.

Now let’s look at what data structures are available to us and what would suit this problem the best.

Oh Array, my old friend, will you help me?

Using an array seems to be a rather straightforward approach.

- We can simply put all the names on the released list in an array.

- Then we sort all the names (the list of names released might be randomly arranged) lexicographically

- And then we can find our name in the list by using a binary search procedure. This would give us the predecessor and the successor.

This seems to be a viable approach to solve this problem. The issue at hand, however, is that the students are never fixed from one exam to another. And so the list that was released for the very first exam would vary dynamically when new students were added and old ones were removed.

We can sort the list for the very first time, and then keep on adding new elements and removing old ones accordingly moving forward.

However, the complexity of adding or removing an element from an array is of the order O(n) . Since the number of students could be very large, and we don’t know how many modifications there would be before some new test, this would take a lot of time and the test would start before we could solve the problem. Remember that the modifications are released just five minutes before the test.

So what other data structure do we have where insertion and deletion can be done very quickly?

Hmmmm, maybe Linked List is my true friend after all

As far as a linked list is concerned, it has it’s own set of problems when dealing with this type of situation. Initially, we need to sort the list of elements lexicographically. Since this is a one-time operation, because it is only to be done for the first exam, the time taken here does not really matter.

From the next exam onwards, only the modifications are released. Adding or deleting an element from a linked list is a constant time operation, provided we know the location of that element in the list.

Finding an element in a linked list is a linear time operation — it takes O(n) . I know there are concepts like skip lists, but why dive into something like this when we can solve this problem in a much better fashion by using another type of data structure?

Enter Binary Search Trees, the new kid in town

Let’s look at how we can model our data using a binary search tree (BST). Then we’ll see how a BST can help us solve the problem we initially set out to solve.

A Binary Search Tree is basically a binary tree with a special way of ordering the nodes.

For a node with key k, every key in the left subtree is less than k and every key in the right subtree is greater than k.

In our case, the keys will be the names of the students.

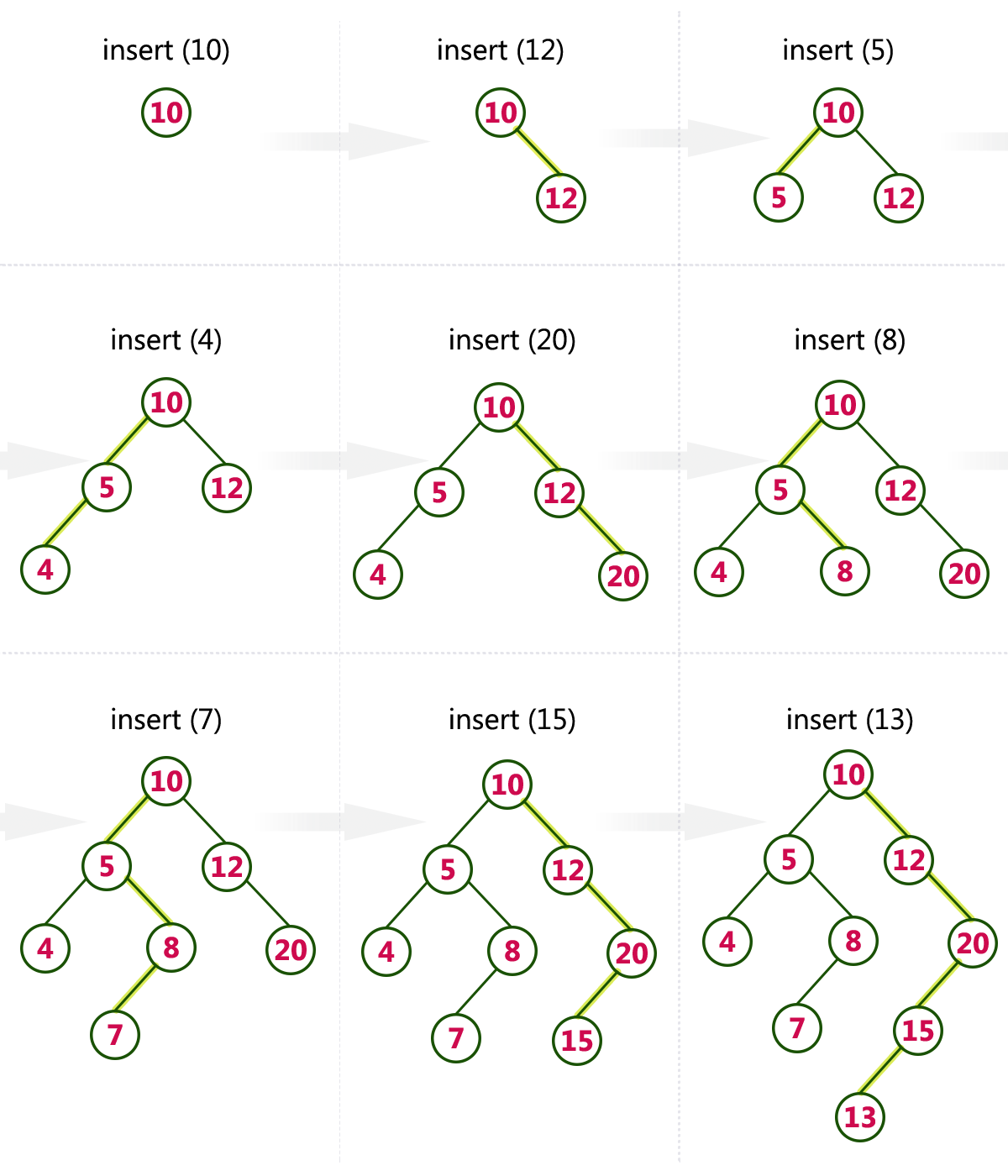

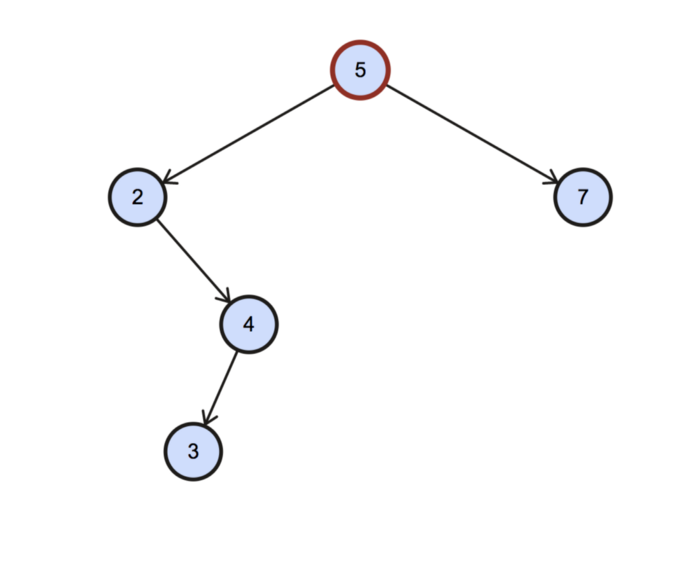

Consider the following example to see how a binary search tree is constructed. This should lend greater clarity to the data structure.

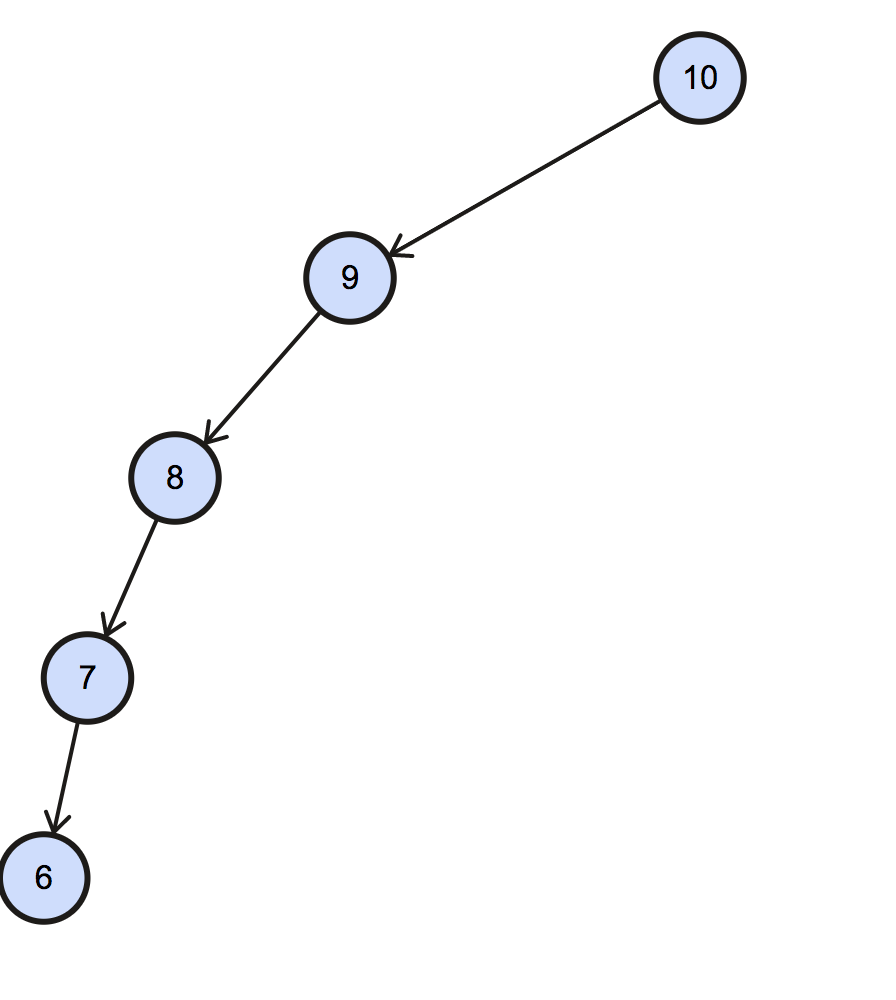

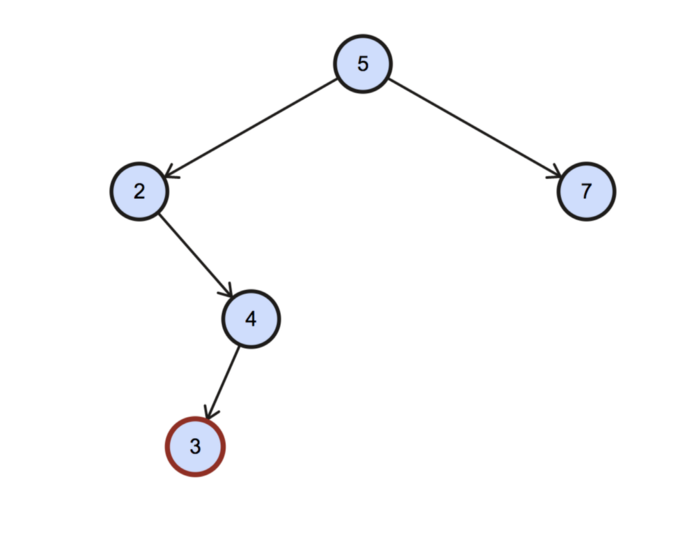

Constructing a Binary Search Tree is not enough. We need to make sure it is balanced. The reason we say that a Binary Search Tree needs to be balanced is that, if it is not balanced, then we can have something like this:

This is known as a skewed binary search tree. If such a thing happens, then the BST basically transforms into a linked list and that is of no use to us. Therefore, we have this notion of keeping a BST balanced so that we don’t run into this problem.

The notion of balanced is defined differently by different approaches, like Red Black Trees or AVL trees. Further explanation of these trees is out of the scope of this article.

Coming back to arranging our data in a balanced BST: the keys to our BST would be the names of the students, and lexicographic matching would be used to determine the structure of the BST.

Suppose that there were a million students taking the test. If our binary search tree is balanced, then the complexity of performing any operation is upper bounded by O(log(n)) .

Hence, for 1 million nodes, the maximum number of nodes to be scanned would be just 14.

That’s a lot of complexity reduction simply by arranging the data in a certain manner. That is the advantage of representing data in a balanced Binary Search Tree.

The main problem with the array-based approach was that we could not efficiently insert or delete an element from the array. And the problem with the linked list approach was that there was no efficient way for us to find an element in the linked list even if it were sorted.

As for a balanced binary search tree, the time complexity to insert, delete, or search for an element is all bounded by O(log(n)) . And this is precisely what makes this data structure extremely exciting.

However, we still haven’t solved our original problem.

Given the name of a student, we want to find out the student sitting right behind and right in front of them. This boils down to finding the in-order successor and predecessor in the given Binary Search Tree.

In-order Traversal and Sorted Order in a BST

An interesting property of the binary search trees is that we can retrieve the elements in the sorted order (even reverse) by doing an in-order traversal over the binary search tree.

So the in-order successor of a node X is the element that comes right after X in the in-order traversal over the given BST. For our cheating problem, this in-order successor would be the student sitting in front of us.

The in-order predecessor of a node X is the element that comes right before X in the in-order traversal (or the element that comes right after X in the reverse in-order traversal) over the given BST. For our cheating problem, this in-order predecessor would be the student sitting right behind us.

In-order Successor in a BST

There are two different cases that we need to handle when finding the in-order successor of a node in a BST.

Case-1

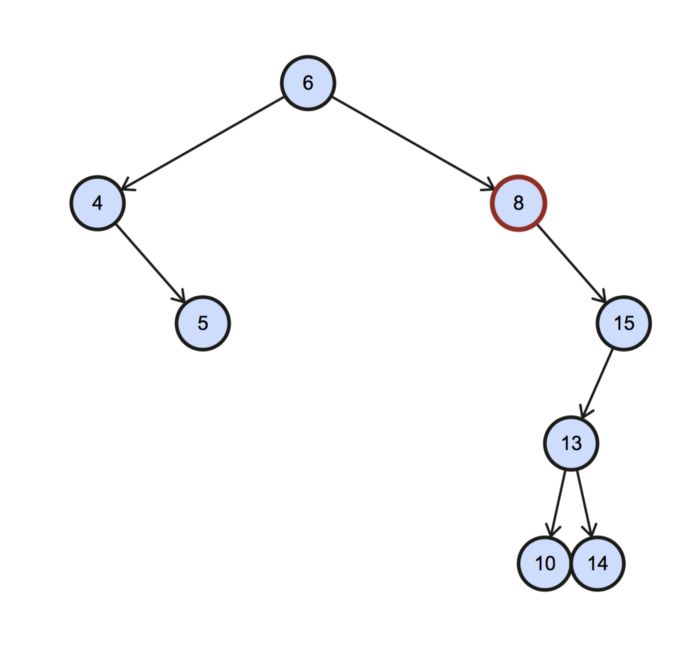

The first case is when the right child exists for the node whose in-order successor we are trying to find. Consider the following example.

Here we wanted to find the in-order successor of the highlighted node 8. Since it has a right child, the in-order successor would be the leftmost node in the tree with a right child, or 15 as the root. So that node would be 10 in this case.

Case-2

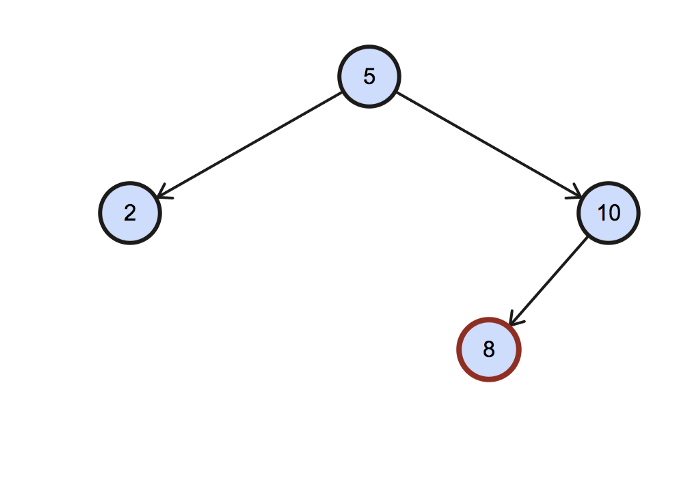

The second case is when there is no right child.

In this case, the in-order successor has two possibilities:

- One is where the node under consideration is the left child of its parent. In this case, the in-order successor would be the parent itself. So for our given case, the in-order successor would be 10.

- The second case is when the current node is the right child of it’s parent. And it doesn’t have a right child. So it is the rightmost node in the BST and it has no in-order successor.

Handling the first case is fairly simple for a binary search tree. For the second case, where the given node does not have a right child (or any parent pointers), we will have to rely on our good ol’ recursion mechanism and do an in-order traversal until we figure out the parent of our given node.

So, the worst case complexity can be O(n) if the case above occurs.

Using this algorithm, we can quickly find out the student who will be sitting right in front of us in the exam.

In-order Predecessor in a BST

This is the exact reverse of the previous case.

Again, we need to handle two different cases when finding the in-order predecessor of a node in a BST. Look at the following diagrams and try to relate the two cases being referred to here.

This is the case where the node has a left child. We need to find the rightmost child of the tree rooted at this left child — the rightmost node in the tree rooted at 2.

No left child. So we need to find the parent.

If you look closely, I’ve just reversed the order of traversal here and the rest of the code is the same as before. (NOTE: this code is used when there is no left child of the node for which we want to find the in-order predecessor).

In-order predecessor becomes the reverse in-order successor.

Well now that you know how you should arrange the class seating arrangement list, go get some solid marks 😜😜😜. Just kidding!! Cheating is bad — don’t ever do it!

Hope you got the main idea behind the different usages for data structures and how to find the in-order successor and predecessor in a BST.

Leave a comment