There are no coincidences in this world.

— Grand Master Oogway

Well, Master Oogway, no disrespect, coincidences do occur and I think they are just God’s way of remaining anonymous. Not just me, Albert Einstein believes this too 😛.

Source: giphy

111, that’s not really my lucky number, so to say.

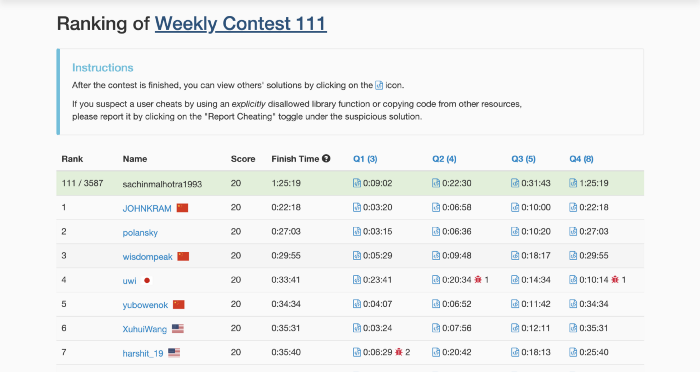

However, this number filled me with joy and ecstasy when I saw it as my rank on the rankings page of the LeetCode contest number 111.

What a coincidence!

That’s the highest ranking in a weekly contest that I’ve achieved so far on the platform. The contest number and the ranking were obviously pure coincidence.

The contest usually consists of an Easy problem, 2 Medium level problems, and a Hard problem.

More often than not, the hard problem is something that requires a lot of algorithmic knowledge and prior practice to be able to pull off during the contest. This contest’s final problem was no exception to this.

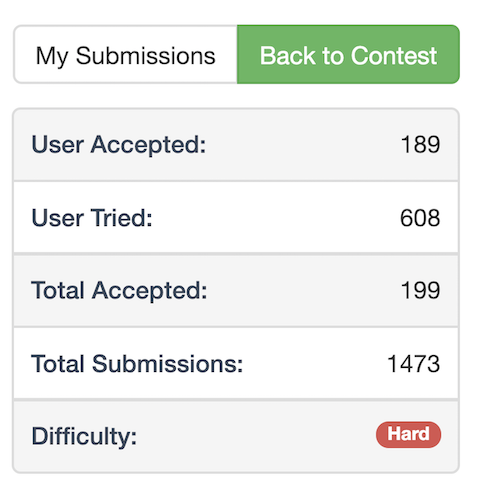

Why do I say it was very hard? Have a look at the number of people who were able to solve it during the contest.

As the title of the article suggests, this problem was to be solved using Bit Masking based Dynamic Programming.

Dynamic Programming is one of the most dreaded algorithmic domains out there. It requires a lot of practice to develop intuition about a dynamic programming-based solution to a problem. I’ve always considered it to be an enhancement to a recursive solution to a problem. The main idea behind dynamic programming in layperson’s terms is:

Avoid repeated computations by caching the results.

Bitmasking as a topic in computer programming is something that I have (and I’m sure countless of other developers out there have as well) feared for a long time. This is one of those topics that will surely take you off balance in an interview and get you a rejection.

Programmers out there generally tend to avoid practicing problems related to this topic simply because it is difficult to build an intuition about it.

Optimizations related to bit manipulations occur in the most unexpected of places. With some practice, I have been able to overcome the fear, so to say, of working on bitmasking-based programming problems.

In this article, apart from describing the solution to the problem I’ve mentioned above, in detail, I will also go over some basics of bitmasking and some programming problems where it can come in handy.

As with any new thing you learn, it’s very difficult to retain theoretical concepts related to bitmasking. Retention is the best when it comes via practice. That is the main aim of this article.

0️⃣ 1️⃣ What is Bit Manipulation? 0️⃣ 1️⃣

A bit is to the computing world what an atom is to human life.

A bit is essentially the smallest unit of storage in a computer. It’s the only unit that a computer understands.

The only information that a bit can store is formed from two different states: 0️⃣ and 1️⃣. Any sort of computation that a computer performs is basically some form of bit manipulation.

Let’s look at a Wikipedia definition for bit manipulation:

Bit manipulation is the act of algorithmically manipulating bits or other pieces of data shorter than a word. Computer programming tasks that require bit manipulation include low-level device control, error detection and correction algorithms, data compression, encryption algorithms, and optimization. For most other tasks, modern programming languages allow the programmer to work directly with abstractions instead of bits that represent those abstractions.

Implementation-wise, one of the most useful and effective low-level optimizations to an algorithm is bit manipulation.

In some cases, bit manipulation can bypass looping over a data structure and give manifolds speed improvement. The only downfall to such optimizations is the code readability and maintenance.

Who wrote this piece of shitty (read lightning fast) code?

That is one scary piece of ☠code ☠

The Basics ✍️

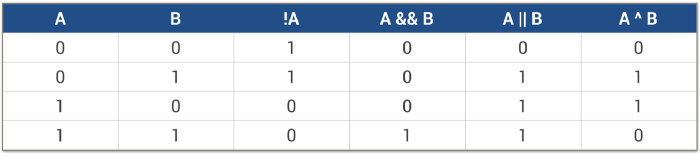

At the heart of bit manipulation are the bit-wise operators:

- And (&)

-

Or ( ) - Not (~)

- XOR (^)

These are the fundamental operators using which we can perform some complicated bit manipulation operations. Hence, it’s very important to brush up on these operators and their truth tables before moving onto some more interesting stuff.

The truth tables show the results for these operators when they operate on 2 bits represented by A and B. The computer has to deal with much more than just one bit of data.

The data processed by the system is generally in bytes or kilobytes or more. How do these operators work on operands represented by for e.g. 8-bits or 16-bits? In such a scenario, the operations are the same, except that they operate on each bit of the arguments. Let’s consider a simple example to clarify this.

A = 11101010

B = 00110101

+-+-+-+- AND -+-+-+-+

A & B = 00100000

+-+-+-+- OR -+-+-+-+

A | B = 11111111

+-+-+-+- NOT -+-+-+-+

~A = 00010101

+-+-+-+- XOR -+-+-+-+

A ^ B = 11011111

In addition to these 4 basic operators, there are two other set of bitwise operators that do come in very handy. Almost all the problems that we will look at in this article will be making use of them to give a huge boost in computational speed. These are the left shift << and the right shift >> operators.

Simply speaking, the left shift operator means multiplying a number by 2 and the right shift operator means dividing a number by 2.

Let’s look at a simple animation to show why these operators are called left shift and right shift respectively.

For demonstrating the left shift operation, we start off with the decimal number 1 and then repeatedly multiply it with 2. As you can see in the binary representation of the resulting numbers, the only 1 in the representation keeps on shifting left one step at a time. That’s why it’s called the left shift operation.

Along the same lines, for demonstrating the right shift operation, we start off with the decimal number 128and then repeatedly divide it by 2. As you can see in the binary representation of the resulting numbers, the only 1 in the representation keeps on shifting right one step at a time. That’s why it’s called the right shift operation.

Now that we are all versed with the basic binary operators, let’s move on to some simple use cases for these operators. We will look at a few examples below. These are not programming problems by themselves, however, they are used a lot as building blocks in a lot of algorithms.

Basic Use Cases 🛠

Counting the Number of set bits

One of the basic utilities for the operators we looked at above is to count the number of bits, set in a given binary representation.

This might not seem an important use case right now, but we will be getting into more details later on and then it will start to seem more meaningful. For now, let’s just count the number of set bits as efficiently as possible.

The first method that we will look at for this, is a bit intuitive. It makes use of the bitwise AND operator. Starting from the least significant bit, we simply check if the bit at each position is set or not and increment a counter accordingly.

The AND operator returns True iff both the bits are True. Let’s look at the code for this.

Yet another way of doing this is by ANDing the number with itself-1 until the number becomes zero. The number of steps taken to reach 0 will be the number of set bits in the original number.

The reason this works is that every time we AND the number with itself-1, one bit gets removed from the number. This goes on until the number becomes zero.

Masking and Unmasking a specific bit

Suppose we want to mask a specific bit in a binary representation_._ This simply means turning off the bit or transforming a 1 → 0 . On similar lines, unmasking simply means the reverse operation on a specific bit.

You might be wondering why this is useful at all. One of the most important use cases for masking (or unmasking) a bit is in set related operations.

We can represent a set of items as an X-bit integer, Xis the number of items in the set. Masking a bit would mean the removal of that item from the set. For a practical application of this, be patient and read on 😛.

XOR is a very versatile operator and it is perfect for the task of masking and unmasking operations.

1 ^ ? → 0

0 ^ ? → 1

XOR outputs 1 when both the bits are opposite and a 0 when both the bits are the same.

Essentially, we can make use of the same masking variable for achieving the set / un-set operation corresponding to a particular bit (the integer in the ? is being called the masking variable).

A ^ (1 << i)

The above operation will lead to masking the bit at index i if originally that bit was set in A and the same operation will lead to unmasking the bit at index i if originally it was unset in A.

We have already seen how to detect if a bit is set or not when we looked at ways to count the number of set bits in a given binary representation.

An important thing to note here is the index. Usually, for data structures in high-level programming languages, whenever we refer to a specific index, we mean the index of a particular element in that data-structure starting from the left end.

What we are referring to an index above is from the right end (the least significant bit in the binary representation has the index 0).

That’s more than enough of the basics for now. Let’s get to some actual programming problems. This will help solidify what we’ve learned so far in the article and also help build up an intuition for solving problems using bit manipulation in general.

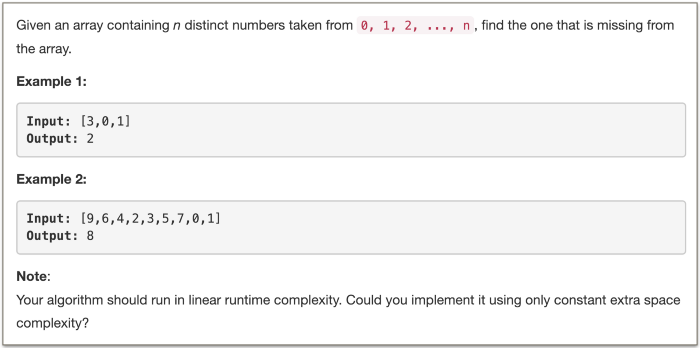

🔭 Missing Number 🔭

There are multiple ways of solving this problem. We can sort the given list of numbers and then iterate from 0..n and easily find the missing number. This will give us a O(NlogN) solution.

Another way of solving this problem is by making use of a dictionary. We simply add all the elements in our list to a dictionary and then we can simply search for the missing number. This is a linear time solution but it makes use of additional space.

Let’s look at how we can achieve a O(1) space, O(N) time solution like a boss 😎 by using bit manipulation.

We will make use the XOR property here to solve this problem. As mentioned before, XOR evaluates to True when the input bits are different and it evaluates to False when presented with the same bits. We are interested in the later scenario. What do you think the following evaluates to?

A ^ A

XORing a number with itself gives us 0. That’s the main idea behind our approach here.

So, what we will do is, we will XOR all the numbers in our list. Let’s call the value we get after this as A .

We will XOR all the numbers from 0..n together. Let’s call this value, B.

By doing this, all the numbers present in the original array will get XORed to their counterparts and will evaluate to 0. The only number left in the end will be the missing number.

A ^ B = missing number

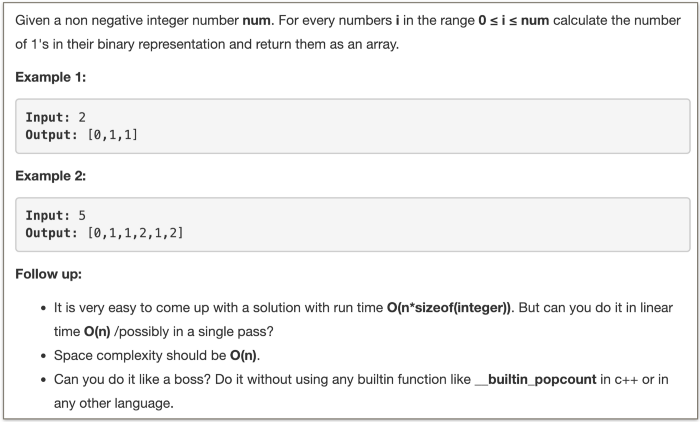

☝️🏼✌️🏼 Counting Bits 🖖🏼 🖐🏼

This is one of those problems where writing down the answer for various test cases and observing the results for patterns really helps. So, we will do exactly that and use the pattern we find to directly arrive at the final algorithm.

Let’s look at the number of 1’s in the binary representation of the first 16 numbers.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

0 1 1 2 1 2 2 3 1 2 2 3 2 3 3 4 1

The pattern being formed above is the following:

An even number, E, has the same number of bits as that of E / 2

An odd number, O, has one more bit than that of O / 2

That’s all there is to see in the results above. This is the algorithm in its entirety. All we have to do is to iterate on numbers from 0..n and use the two rules above and we solved the problem like a boss 😎.

If you paid attention to the core idea of dynamic programming discussed during the beginning of the article, you’d know that this here, in essence, is a dynamic programming problem.

We make use of the result for a previous subproblem (smaller number) to calculate the answer (number of set bits) for the current subproblem.

On the face of it, we don’t need any bit manipulation as such to solve this problem. It can be solved by simple if-else clauses and a for loop.

So, this is not really a bitmasking + dynamic programming kind of problem.

Let’s look at a simple solution based on the ideas above.

This is a perfectly good way to solve this problem. For every index, i, we check the number of bits in the number i / 2 and also add 1 if the current number is odd.

We can, however, solve it in a geekier way, so to say using bit manipulation. The two operations being performed are:

- division by 2 and

- checking if the number is even or not.

We have already seen the use of the right shift operator, >>, for division by 2.

As for the second operation, we can simply check if the least significant is set or not. If you notice, all the odd numbers have their least significant bit set. While the even numbers don’t.

We have already seen how to check if a particular bit is set or not using the AND operator. Let’s see a geekier 🤓 version of the above code.

If you look at the runtimes for both the programs, they’re almost the same. A major chunk of the time is consumed by the construction of the output array.

Bitwise operations are always optimized and are faster than other higher level programming constructs.

⛩ Maximum Product of Word Lengths ⛩

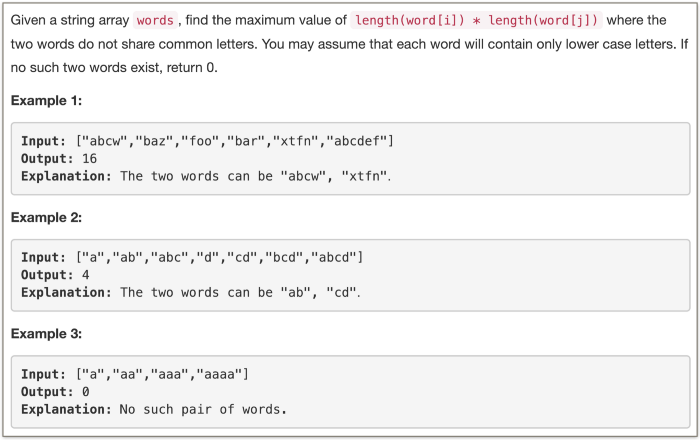

There’s good news and bad news. The good news is that a slightly optimized version of the brute force algorithm will get your code accepted on the platform.

The brute force way is to check all the pairs of words and for each pair, check if there are any common characters between them. For all such pairs that don’t have any common characters, record the maximum value of len(word1) * len(word2).

The bad news is that this algorithm is extremely slow. Let’s look at the percentage of solutions on LeetCode which this brute force algorithm is able to beat.

Shame on you, Sachin!

That’s not the kind of stats you want to see for your submission. If you’re someone who simply wants to solve a problem, then your job here is done. Nothing more to do. But, if you’re like me and if you want to make this dog stop 😅, then read on!

Let’s look at the time complexity for this brute force algorithm before moving onto a much more optimized solution using bit manipulation.

We consider all possible pairs of words from the given array. Considering there are N words in the given array, we will get O(N²) complexity right off the bat.

Other than that, we have a dictionary containing sets of characters for each of the words in the dictionary. Considering the size of the alphabet to be 26 (lowercase alphabets only), each set can potentially be of size 26.

For each pair of words, we perform a set intersection to check whether the two words have any common characters or not. Set intersection takes linear time and hence, the overall complexity for this algorithm would come out to be O(26N²) which is essentially O(N²).

It turns out that we can’t get rid of the part where we have to consider each pair of words from the given array. So, we can’t get rid of the O(N²) part of the algorithm.

The portion that we can get rid of, however, is the part where we compare two words and see if they have any common characters. That constant 26 slows down the algorithm a lot.

An important thing to note here is that the question simply cares about common characters and not their frequency or their order.

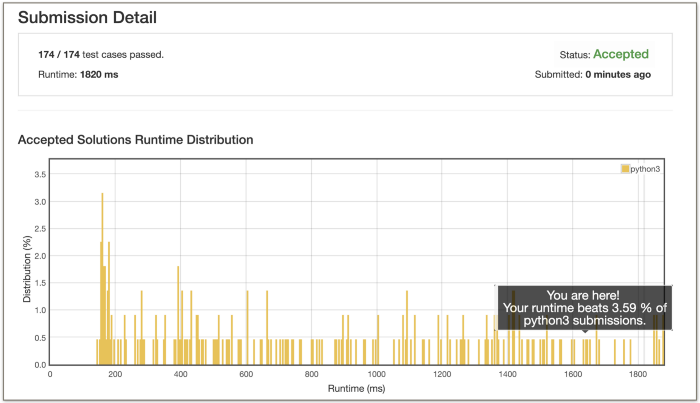

What if we simply use a bitmask to represent the characters in a word?

What we can do here is to have a bitmask consisting of 26 bits to represents the characters belonging to a particular word. Let’s look at such a representation for a few words to make things clearer.

Hope the above figure makes it clear what we mean by a bitmask representing a corresponding word. Once we have these bitmasks for all the words, all that remains now is to check if two words have any common characters or not.

If two words would have any common characters, then the corresponding bits for those characters would be set in the bitmasks for both the words.

Hence, all we have to do is to do a bitwise AND of the bitmasks representing two words and check if we get a 0 or not. If we do end up getting a 0, that would imply no intersection and that is precisely what we are looking for.

For e.g.

Let's consider two words "hello" and "jack"

The bitmask corresponding to "hello" will have the bits for 'h', 'e', 'l', and 'o' set.

The bitmask corresponding to "jack" will have the bits for 'j', 'a', 'c', and 'k' set.

Since these words don't have any character in common, the bitwise AND of their bitmasks will give a 0.

Had there been any common characters between them, then both their bitmasks would have set bits at the same indexes (corresponding to the common letters) and hence we would get a non-zero bitwise AND.

Let’s look at the code for this modification in the algorithm we just discussed.

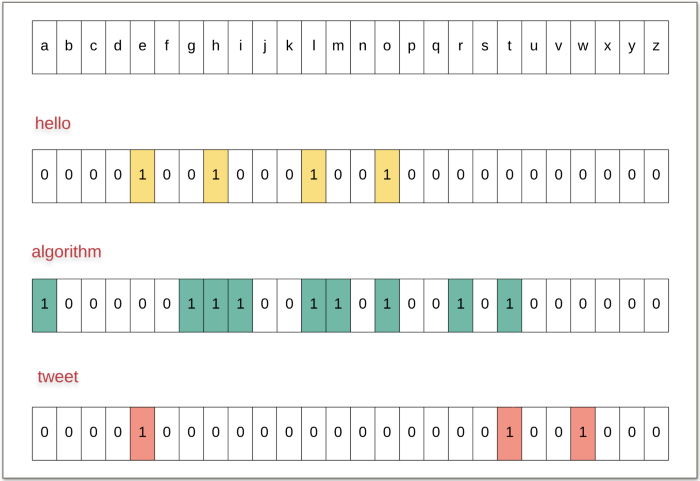

Bitwise operations are super quick. Let’s look at the performance of this algorithm on the LeetCode platform to corroborate the quickness of bit manipulation.

Not bad, right? We improved the runtime for our program from 1820 ms earlier to 712 ms now. That’s a huge improvement, isn’t it? It turns out, we can improve this algorithm even further.

The improvement can be made because of the fact that two different words can have the same bitmask.

For e.g. hello and llohhel both would have the same bitmask. We can store the longest word for a given bitmask since all we care about is maximizing the product of word lengths.

Let’s look at the code after incorporating this improvement.

By doing this very optimization, the runtime comes down to 208ms 🎉🎉🎉

Set Representation using Bitmasking

We introduced an idea in the previous problem which will be crucial in the next two problems that we will discuss. Essentially, we used the idea of bitmasking to represent elements belonging to a set.

In the previous article, we considered a set of 26 alphabets and we resented that by using a bitmask containing 26 bits. A 0 at a particular index in the mask would represent set exclusion whereas a 1 would represent set inclusion.

This idea is very crucial for dynamic programming problems that deal with subproblems involving a subset of numbers. We can’t really cache a subset of numbers. A set is not a hashable data structure.

For e.g. suppose we have an array of numbers [4, 3, 6]

Let's look at all possible subsets of this array.

[]

[4]

[3]

[6]

[4, 3]

[4, 6]

[3, 6]

[4, 3, 6]

For dynamic programming problems where intermediate states are defined by these subsets, we need a memory efficient way of performing caching.

What do we do in such a scenario?

This is where we have bitmasks come in. They are memory-efficient ways of representing subsets of elements. Let’s have a look at how we can represent the subsets above using bitmasks.

Since we have 3 elements in our given array, [4, 3, 6] we can make use a a 3-bit number for representing each of these elements. An empty subset would be represented by 000. Let's look at each of the subsets along with their bit representations.

000 -->> []

001 -->> [6]

010 -->> [3]

011 -->> [3, 6]

100 -->> [4]

101 -->> [4, 6]

110 -->> [4, 3]

111 -->> [4, 3, 6]

Depending upon the problem’s constraints, we can make use of a bitmask. For e.g. in the previous problem, the alphabet set was limited to the size 26. A lot of programming problems that have small array sizes and involve dynamic programming that require you to hash subsets, usually are an indication of bitmasking-based approach.

A 26-bit mask, e.g. in the previous problem, is essentially an integer and we can simply cache that integer in a dictionary. This saves on the memory footprint of the algorithm and greatly cuts down on the time complexity for the algorithm since bit manipulation is very efficient. We can easily include and exclude elements from the subset by masking and unmasking corresponding bits from the mask.

Let’s look at another problem based on this idea before we finally discuss the star problem of this article.

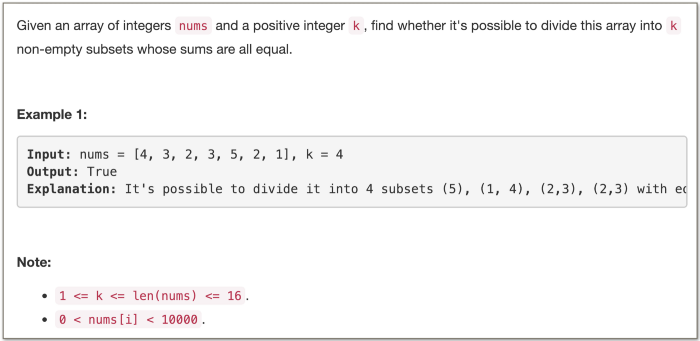

🗄📂Partition Array to K Equal Sum Subsets 📂🗄

This is just one of those questions that begs you to use bitmasking. Notice the size of the array. It’s just 16 elements. If we consider a bitmask to represent the elements in an array, we’d have a 16-bit integer at our hands.

That means, to represent all the possible subsets of a given array, we’d have 2¹⁶ possible integers. We don’t really need actual subsets. All we need is a bitmask telling us the elements belonging to that subset. Based on this idea, let’s look at dynamic programming-based approach to solve the above problem.

The problem statement only asks us if a k-equal-sum partitioning is possible or not. It doesn’t ask us to return the actual partitioning. That makes the problem a whole lot simpler.

We don’t care which partition an element belongs to as long as the overall sum of a partition is what total_sum / k.

As we’ve mentioned in the above paragraphs, we will be using a bitmask to represent the elements of the array.

We will use the individual bit states of the mask to identify which numbers have already been assigned a partition and which ones still remain to be assigned one. We can only assign a number to a partition if after adding it to that partition, the total sum remains <= total_sum / k .

If the sum, S, of all the elements of the array is divisible by k, we have to complete k — 1 partitions since the last partition will automatically fall into place. In case the total sum is not divisible by k , then such an equal sum partitioning is not possible.

Why dynamic programming?

Before looking at the code for this problem based on the ideas we’ve discussed above, it’s important to understand how dynamic programming fits into the picture. We’ve already seen why bitmasking would come in handy. But where exactly does dynamic programming fit in?

Recursion is a natural fit for the problem since we have got a set of N elements and we need to partition them into k different subsets all of which have an equal sum.

Since we don’t really know what partition a number should belong to, we have to try out all the options. That means, for a given partition, we try adding all available numbers recursively (within the constraints of the partition sum) and see which choice leads us to an answer.

The recursion would be based on the following three variables:

- the

number of partitionsremaining. - the

maskrepresenting what elements in the original array are unassigned. - and the current

partition sum.

As we all know, for any problem to be classified as a dynamic programming problem, it should have the following two properties:

- Optimal sub-structure ~ which simply means that the original problem must be breakable into subproblems and optimal solutions to the subproblems should be usable in a way to find the optimal solution to the main problem.

- Overlapping subproblems ~ which mean there are multiple recursive calls to the same subproblems and to avoid repeated computations, we can cache the results for our subproblems.

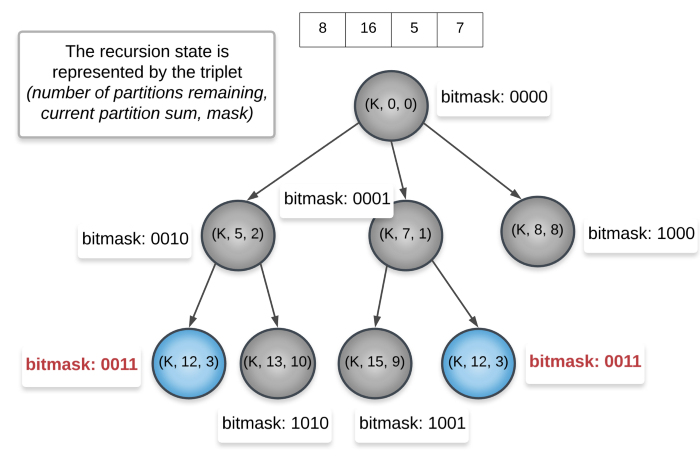

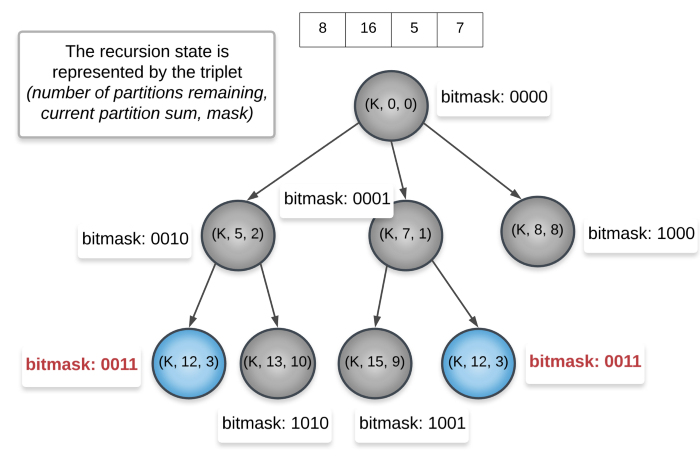

Let’s look at the recursion tree for this problem to understand if we have any overlapping subproblems. We already have the first property satisfied.

In the above recursion tree, we consider K = 2. That means we need 2 partitions each of sum 18. Since we never reach 18 in the tree above, the K never gets reduced. This is just a part of the recursion tree and the complete version.

We can clearly see two recursion states getting repeated. We get the same mask 0011 twice. We can simply store the result once and then re-use it later on.

Now let’s look at the code for based on bitmasking + dynamic programming.

Now we are finally ready to look at the main problem of this article. The problem that is not as straightforward in its bitmasking application as the current one and the previous one.

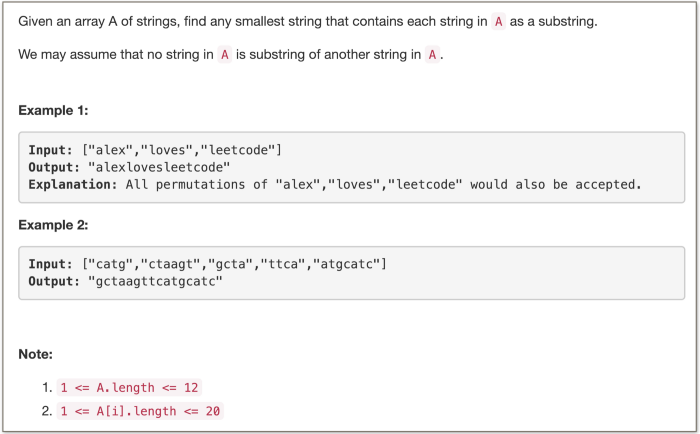

🔥 Find the Shortest Superstring 🔥

What do you think the simplest way of forming a superstring is?

You simply take any permutation of the given words and all of these permutations will be valid superstrings.

However, the question doesn’t ask us to form any superstring. It asks us to form the shortest superstring covering all the words.

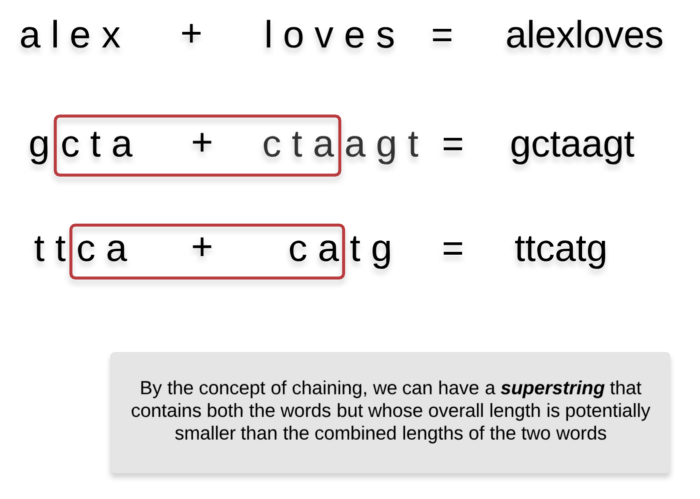

For this problem, we will explore the idea of chaining words together. Intuitively, you can consider the idea of chaining as set union.

Let’s consider two different set of elements and then look at the combined set containing all their elements together i.e. the union set.

As we can see above, whenever we do a union over two sets, the common elements only appear once. We will adopt a similar idea with chaining two words together.

Essentially, when chaining words A and B together, we will only consider the common portion between the suffix of A and prefix of B exactly once. Let’s look at the diagrammatic representation for chaining of two words.

This is an important concept that will come in handy for solving this problem. So as to avoid repeated computations of finding out the common portion between two words which are being chained together, we will do some preprocessing.

We will find out the length of the suffix of A that overlaps with the prefix of B where A and B are being chained together. We will do this for all the pairs of words in our given list. In Python, given a string S, we can make use of S[i:] to obtain all the suffixes and S[:i] to obtain all the prefixes. We make use of this for our preprocessing below.

In the snipped above, s“words” is a list of words that we process. The function “form_edges” is called to compute the common chaining length between all the pairs of words. The function “longest_pref_suf” simply computes this common portion between a given pair of words, A and B.

Now that the idea of chaining is clear, we can move onto the next part of the problem where we explain why this problem can be solved recursively.

Why Recursion?

Now that we are familiar with the concept of chaining, we know that whenever we chain two words together, the new word formed can be shorter than the combined lengths of the two original words.

Extending this idea to all the words in the given list, we have to form a superstring that will be formed by chaining one word after the other until we are done with all the words.

The important question here is, in what order should the words be chained together?

For the three words aabc , hjaa, and chuj the chaining order hjaa → aabc → chuj = hjaabchuj is better than aabc → hjaa → chuj = aabchjaachuj since the former gives a superstring of length 9 as opposed to 12 in the latter order.

So, the chaining order determines the overall length of the formed superstring.

We will be trying out all possible arrangements for the superstrings using the given list of words and choosing the shortest one.

That seems legit, but why dynamic programming? 🤔

Instead of relying on a recursion tree for explaining the need for dynamic programming, we will look at an example that will explain the same idea.

Suppose we are given a set of 5 words [A, B, C, D, E] and we are to form the shortest superstring that contains all the words.

We already know that we are solving this problem recursively. Suppose in the middle of our recursion, we are already done deciding the chaining order of the first 3 words. Let’s say this ordering was B → A → C . Now, we need to find out the best way to chain D and E after C so that the overall superstring length is minimized.

Let’s say that in our recursion we found that C → E → D was the best chaining order. We don’t know yet if the superstring formed via B → A → C → E → D is the shortest one. However, we know that C → E → D is the best chaining order for the three words C, D, and E .

I know it’s gotten tiring, but keep reading 😛

Suppose now we arranged the first three words a little differently in our recursion (a separate recursion path) and now we have A → B → C and we have to recurse again to find out the best possible arrangement for E and D . However, we already know from above the best possible arrangement is C → E → D . Why calculate this again? This is where dynamic programming comes into the picture.

That’s it? Go on. Explain some more.

Nah, let’s now look at the the Python code bringing all these ideas together.

Uh oh! Where the heck is bitmasking in all this?

Ok ok, let’s get to bitmasking 🎉

Let’s rephrase the problem in a slightly different manner that will make the requirement for bitmasking very clear.

Given a set of N elements, we need to find a suitable arrangement for them that will minimize a certain metric. Since we are relying on dynamic programming, we will be caching results for subproblems_._

Our subproblems will be represented by the subset of these N items. As we’ve seen in this article and especially in the previous two problems, it’s difficult to cache subsets as it is.

In case the problem constraints are small, we can represent the elements of the list using a bitmask and use that for caching purposes.

After all, a bitmask is just a number.

Let’s finally get to the code for finding the shortest superstring given a set of N words.

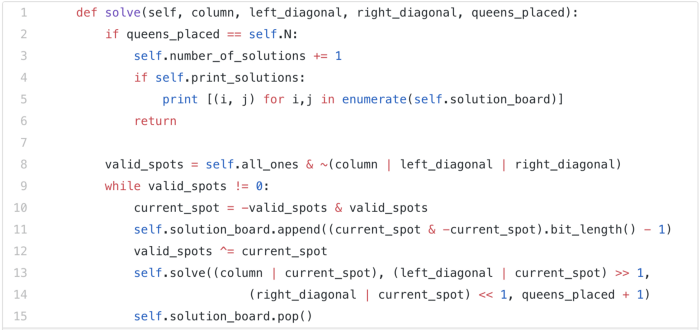

- Line 3 ~ The initial mask is composed of all 1s. That implies all the words are available for chaining. If the mask becomes 0, that means no word is left for chaining. So, the length of the superstring would be 0. This is the base case.

-

Line 7 ~ If you’ve paid attention to the example involving 5 words

[A, B, C, D, E]from before, you know that the opportunity of caching arises when we have the two wordsD and Eto be chained together following C.Thus, we need to know the previous word in the superstring so far so as to attach the rest of the words. Hence,_

_prev_i__, which represents the index in the original array of the previous word in the superstring is also used for caching purposes apart from the mask. - Line 12, 15 ~ We always check all the given set of words and only consider those as options for the current step in our recursion which have not been previously used. We make use of bitmasking for this. To see if a word has been used or not, we simply check if the bit at the corresponding index in the mask is unset or not.

- Line 18 ~ Makes use of the preprocessing we did earlier. For the word to be chained / attached to the word at index

prev_i, we know the amount of overlap between the two. Thus, if we decide on considering the word at indexias the next word in our recursion, the amount of length it will add to our superstring would belen(A[i]) — overlap between the words A[prev_i] and A[i]

All this is fine and dandy, but wasn’t the original question asking for the superstring itself and not just the length of the shortest superstring?

Am I shying away from solving the entire problem? Of course not!

The function recurse simply returns the length of the shortest superstring and not the superstring itself. The problem statement, however, asks us to find out the shortest superstring.

If you look at the code carefully, you’ll notice a parent dictionary. At every step in our recursion, we have multiple options of words which can be chained to the current superstring (thus extending it). We use the parent dictionary to store the word at each step that gave the best answer (shortest length).

For a given mask — which tells us which words have already been chained together — and a given previous word (prev_i), the parent dictionary stores the next word that in the superstring that gives the optimal answer.

We will use this dictionary to backtrack and form the shortest superstring.

In the end, that’s one of the best sights for a competitive programmer, especially if it’s for a hard problem in a timed competition.

Conclusion 🍻🍻

- Operations on bits are highly efficient and they are generally performed in parallel via optimized system level instructions.

- It’s difficult, but not impossible, to write clean, understandable code involving bit manipulations.

AND,OR, andNOTare the three fundamental bitwise operators.- The

left-shift <<and theright-shift >>operators are used for multiplication or division by 2. - The

XORoperator is a versatile operator that can be used in many different programming problems. It returnsTrueonly when both the bits are opposites andFalseotherwise. - Dynamic Programming-based solutions involve some sort of caching for the results of subproblems. The subproblems are represented by a set of variables. These variables are not necessarily primitive data types.

- Bitmasking comes in very handy in dynamic programming problems when we have to deal with subsets and the list/array size is small. A mask (having all 0s or all 1s) can represent the elements of the set and setting or unsetting a bit can mean inclusion and exclusion from the set.

- If the array/list/set size is, say, around 20, then you’d have 2²⁰ possible bitmasks which comes out to be almost a million of them. It’s not always the case you will encounter all of these bitmasks in a test case. However, that’s the maximum possible number.

- We have to be careful about when to use bitmasking. We can’t have a 100-bit mask as that would be computationally intractable.

- For a solution to be eligible for dynamic programming, it should satisfy the optimal substructure and the overlapping subproblems properties. Usually, through some practice, you can start to identify if the problem at hand will have a DP based solution or not.

It’s been a long article and one that I’ve absolutely loved writing. If you’ve read this far, then you’ve probably found this article really helpful. Do spread some love by sharing it as much as possible and destroy that clap button! 👏

Leave a comment